Abstract

The most suitable donor for allogeneic stem cell transplant is still a matter for debate when there is no matched related or unrelated donor. In this setting, information comparing MMURD vs. HAPLO remains scarce and do not show differences between both sources (Piemontese, S et al., Hematol Oncol. 2017; Shem-Tov N et al., Leukemia 2020; Battipaglia G et al., BMT 2022). This study analyzes the outcomes of HAPLO vs. MMURD stem cell transplant recipients in reduced intensity conditioning scenarios (allo-RIC) in a retrospective analysis from the GETH-TC study group.

Methods: Consecutive patients receiving a first allo-RIC between 1/2012 and 3/2021 at 9 GETH/EBMT centers with HAPLO or MMURD (mismatch at HLA-A, B, C, or DRB1 by molecular techniques) were included. Patients undergoing HAPLO received post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCY) based graft vs. host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis associated with rapamycin, tacrolimus, or cyclosporine, +/- mycophenolate. For MMURD, prophylaxis was diverse, including PTCY. Baseline characteristics and outcomes were compared according to the donor type through logistic regression. To balance the two groups, the Propensity Score Weighting method was performed with the variables that were significant in the logistic regression. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the HR using the Cox model.

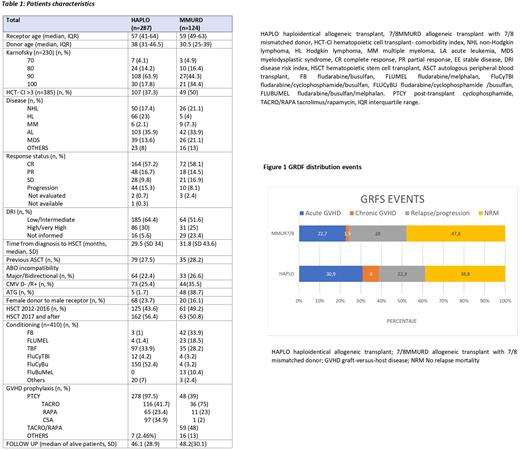

The primary objective was the comparison of the aGVHD III-IV or severe chronic GVHD-free/relapse-free survival (GRFS). Secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), relapse/progression-free survival (DFS), non-relapse-related mortality (NRM), relapse, and acute and chronic GVHD.

Results: A total of 411 patients were included, 287 HAPLO and 124 MMURD (Table 1), with a median follow-up of 46.1 and 48.2 months, respectively. The GRFS at 24 months was similar in both groups, 48.5% vs. 53.9% in HAPLO and MMURD, respectively [HR 0.9, P=0.79). There were no differences in 2 year-OS 58.9% vs. 60.7% (HR 1.04, P=0.93), or in 2-year DFS 55.1% vs. 55.8% (HR 1.05, P=0.9). Similarly, NRM (32.3% vs. 32.1% (HR 1.09, P=0.85) and relapse (18.6% vs. 17.9% (HR 0.96 [95%CI 0.31;2.96] P=0.94) did not present statistically significant differences between HAPLO and MMURD. In addition, there was no difference between groups in time to neutrophil (19 days [95%CI 18;20] HAPLO vs 18 days [95%CI 15;19] MMURD, P= 0.08) and platelet engraftment (27 days [95%CI 23;29] HAPLO vs 20 days [95%CI 13; 33] MMURD, P= 0.15). Regarding 2-4 acute GVHD, the incidence at 6 months was 51.7% vs. 63.2% in the HAPLO vs. MMURD recipients (HR 1.44 [95%CI 0.8; 2.6], P=0.23), without significant differences in 3-4 acute GVHD grade. Seventy-seven HAPLO patients and 42 MMURD patients developed global chronic GVHD, with no significant differences in incidence between groups. Remarkably, MMURD (1% [95%CI 0; 2.6]) had lower incidence of severe forms of chronic GVHD than HAPLO (6.7% [95%CI 2.5; 10.6]) (HR 0.11 95%CI [0.02;0.57], P=0.01). When the analysis was restricted to PTCY-based prophylaxis patients (48 MMURD vs. 287 HAPLO), the outcomes were similar, with a significantly lower incidence of severe forms of chronic GVHD in the MMURD group. Finally, events defining GRSF were similarly distributed between both groups (Figure 1), except for chronic GVHD. However, the latter had a low incidence in both groups, so this difference did not impact the primary endpoint.

Conclusion: In this cohort of patients, no differences in terms of OS, DFS, NRM, relapse, or GRSF were observed between HAPLO and MMURD. Transplantation with MMURD was associated with less severe chronic GVHD, even when considering the group of patients with PTCY prophylaxis exclusively. This advantage of MMURD compared to HAPLO is not translated into an improvement on the GRFS.

Disclosures

Fox:Novartis: Consultancy; Sierra Oncology: Consultancy; BMS: Honoraria; AbbVie: Consultancy. Cabirta:Jazz: Honoraria; Janssen: Honoraria; AstraZeneca: Honoraria. Sampol:GSK: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.